Don't Hide In The Garage While You Build Your Product

A prototype is not the same as an MVP (and why you shouldn't hide in your garage while building it)

Two brothers stood together in the field in Kitty Hawk, South Carolina, waiting for the conditions to be just right. For hundreds of years, brilliant inventors had been dreaming of this moment. Yet the promise of powered flight had so far remained just a dream. On this day, Orville and Wilbur Wright would test their latest design: an airplane (though they didn't call it that) that could carry a pilot and was powered by an engine.

And it flew! For twelve glorious seconds, the Wright Flyer took flight over the ground. It was the first time a human had lifted their feed from the ground in a powered heavier-than-air aircraft.

Would you say that the Wright Flyer was a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)? I bet most people would say so. But you'd be wrong.

The Wright Brothers Flyer was not an MVP. It was a prototype. The first Wright Flyer was unstable, difficult to maneuver, and prone to pitching. Even though it did prove the concept of powered flight, it was not ready for its first customers. In fact, the Flyer was one of many heavier-than-air prototypes that had been developed since the 1640s, and many more prototypes that would be built. While Orville and Wilbur are largely credited for the invention of powered aircraft, they had little to do with the actual viability of aviation and air travel.

These first wartime airplanes were truly Minimum Viable Products. Airplanes solved a problem and the militaries of the world were quick to apply this new technology to the battlefield. The first really viable aircraft began to appear during the run-up to World War I, when airplanes began to do aerial reconnaissance and photography. It didn't take long to figure out how to synchronize a trigger to the propeller and mount machine guns to the front of the airplane.

While they were indeed very minimum (the Fokker Dr.1 Triplane flown by the infamous Red Baron sported an open cockpit and direct flight stick controls), they were also viable: the Red Baron was credited with over 80 kills in this aircraft.

What is a prototype?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a prototype as "an original model on which something is patterned", or "a first full-scale and usually functional form of a new type or design of a construction (such as an airplane)"1.

The purpose of a prototype is to prove if something is possible, while an MVP is designed to test if something is commercially viable.

The Wright Flyer was a prototype, but it wasn't commercially viable. The Red Baron's Fokker Dr.1 was a true Minimum Viable Product.

Let me be clear: there is nothing wrong with prototyping. Like Orville and Wilber, you may actually be developing something truly special that needs to go through the prototyping process.

But the vast majority of MVPs that we see today are not that—they are actually prototypes.

The Myth of the Garage Genius

We tend to idolize the garage genius: the eccentric inventor who holes up in the garage, working on some mysterious invention, and then finally one day emerges in a puff of steam and smoke exclaiming “Eureka”!

In fact, very few actual products are shipped this way. Eureka moments are reserved for giant technical leaps produced by the likes of Leonardo DaVinci, Nichola Tesla, and the Wright Brothers.

After the first burst of creative intensity, a new technology must be brought to market.

Unfortunately, a lot of startup founders act like mad scientists. They hole up in their basement or home office writing code for months and months, planning a glorious public launch of their new product.

Only, the glorious launch is more likely to turn into a fizzle.

It's a mistake I've made myself, as have countless other entrepreneurs: if you build it they will come. Except that it's not true. If you build it you still have to get it to market. In the best case, if you've built the right product and a market actually exists for it, you can get your product to market by throwing gobs of money at marketing, or by having a crack-shot growth marketer on your team.

A better way is to build your market into your product.

You can think of the process of building a Minimum Viable Product as building your market into your product. Through the MVP process you are exposing a market problem, identifying individuals who experience that problem or pain, applying a solution to that problem, and then delivering that solution to people who can pay for it.

What is a Minimum Viable Product?

Let’s look at what the phrase MVP—Minimum Viable Product—stands for:

Viable

I want to talk about Viable first because it is the most important word in the phrase. In order for your MVP to work it has to be viable. Viability can be proved in many different ways, depending on the product. Your product must prove that 1) there is a customer segment who 2) has a problem that 3) your product will fix. In some way, it has to deliver value to the customer; in other words, it has to be worth paying for. And it has to prove that your product will deliver value to you: it has to prove that it can make you money. The goal of an MVP at this point is not necessarily to make a sustainable stream of revenue, but to prove that the value that it promises can be delivered to the people who need it.

Minimum

An MVP is minimum because it must reduce your risk. Nobody can afford to build a maximum viable product. And that wouldn’t make sense anyway because the first point of an MVP is learning, and the second point is to discover if your solution solves a real problem that is worth paying for. Your goal is to expend the least amount of energy and resources as possible on your way to a feature-complete product. As your product matures layers of complexity will be added to it, but at each stage the goal should be to add the least amount of code and complexity that is required. This minimalism should not be construed as laziness or stinginess; rather the goal of minimalism is to reduce waste and risk.

Product

It has to be a product. It can’t be fake, or hollow, or a sham. It has to actually do what it says on the tin. Now, what do we mean by this? The product must deliver value to your customer in some way. It doesn’t matter if you’re using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or if you have an army of friends paid in beer and potato chips working nights and weekends to fulfill orders (the Wizard of Oz), or if you’re piggy-backing on someone else’s technology (OPT). How you supply the solution is irrelevant, as long as the customer gets value out of your solution. You can scale later. But you can’t fudge your way to a successful MVP.

If you're interested in some practical examples of tried and true MVPs from real startups, download our "Every MVP Idea Ever" ebook, below. You'll learn about

- Other People's Technology

- Dogfooding

- The Wizard of Oz

- Flintstoning

- The Concierge

- The Imposter

- … and more interesting startup MVP ideas.

How do you build an MVP?

What’s the best way to build an MVP?

There isn’t one way to build a Minimum Viable Product. What your MVP actually is will depend on your project and the stage where you are with your business. An MVP isn’t necessarily static; your MVP will likely evolve (and you should expect it to). Think of an MVP as clay on a potter’s wheel that changes shape over time.

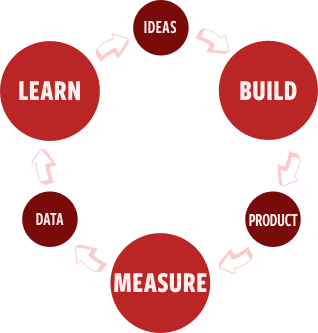

While changes in project scope can blindside traditional projects, with MVP development we expect and embrace these changes. Practically speaking, we do this by borrowing a page from the Agile project management playbook: the Build-Measure-Learn cycle.

The Build-Measure-Learn cycle works like this: it starts with an idea. We build something as small as possible to test the idea: the product. We then measure. This might mean internal testing—trying to apply the product to our own problems, user testing—letting users use the product while we watch and take notes, or even offering the product for sale. From the Measure phase we collect data. We then examine the data and try to learn from it. We use that learning to inform our ideas, which are then fed back into the Build process.

When we go through this cycle again and again, each iteration brings us closer to a shipping product.

Each iteration of the Build-Code-Learn cycle brings us closer to a shipping product.

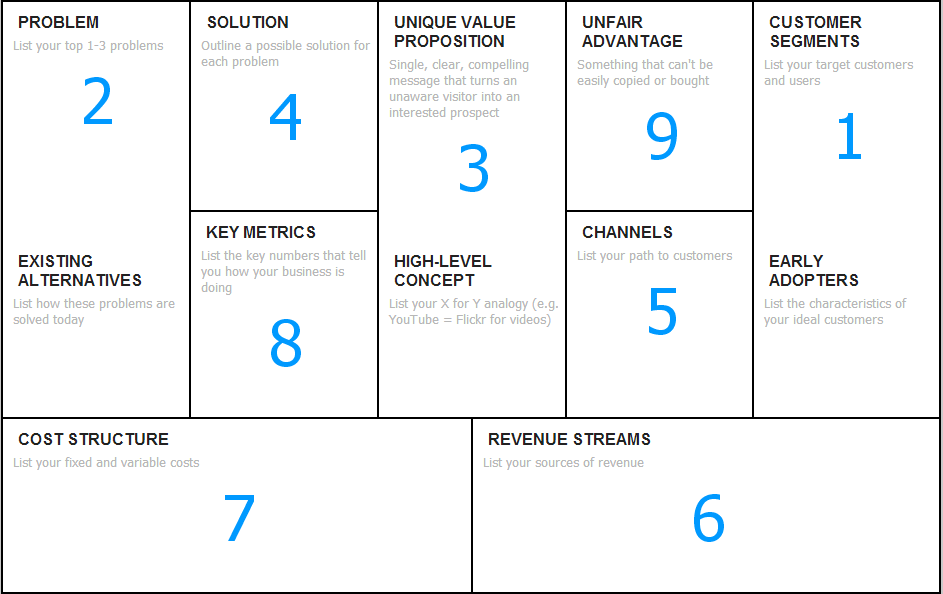

Using a Lean Canvas to Guide Your MVP

The best first step in creating an MVP is to use the Lean Canvas exercise, developed by Ash Maurya. We highly recommend Ash's book Running Lean, though it's not required to do the exercise. You can go to leanstack.com to complete the Lean Canvas exercise for free.

The Lean Stack website provides an excellent video tutorial for each segment of the canvas. Watch each segment and fill out the canvas as you go. You'll be surprised how quickly you can whittle down to the basics of your MVP.

Define a Critical Path

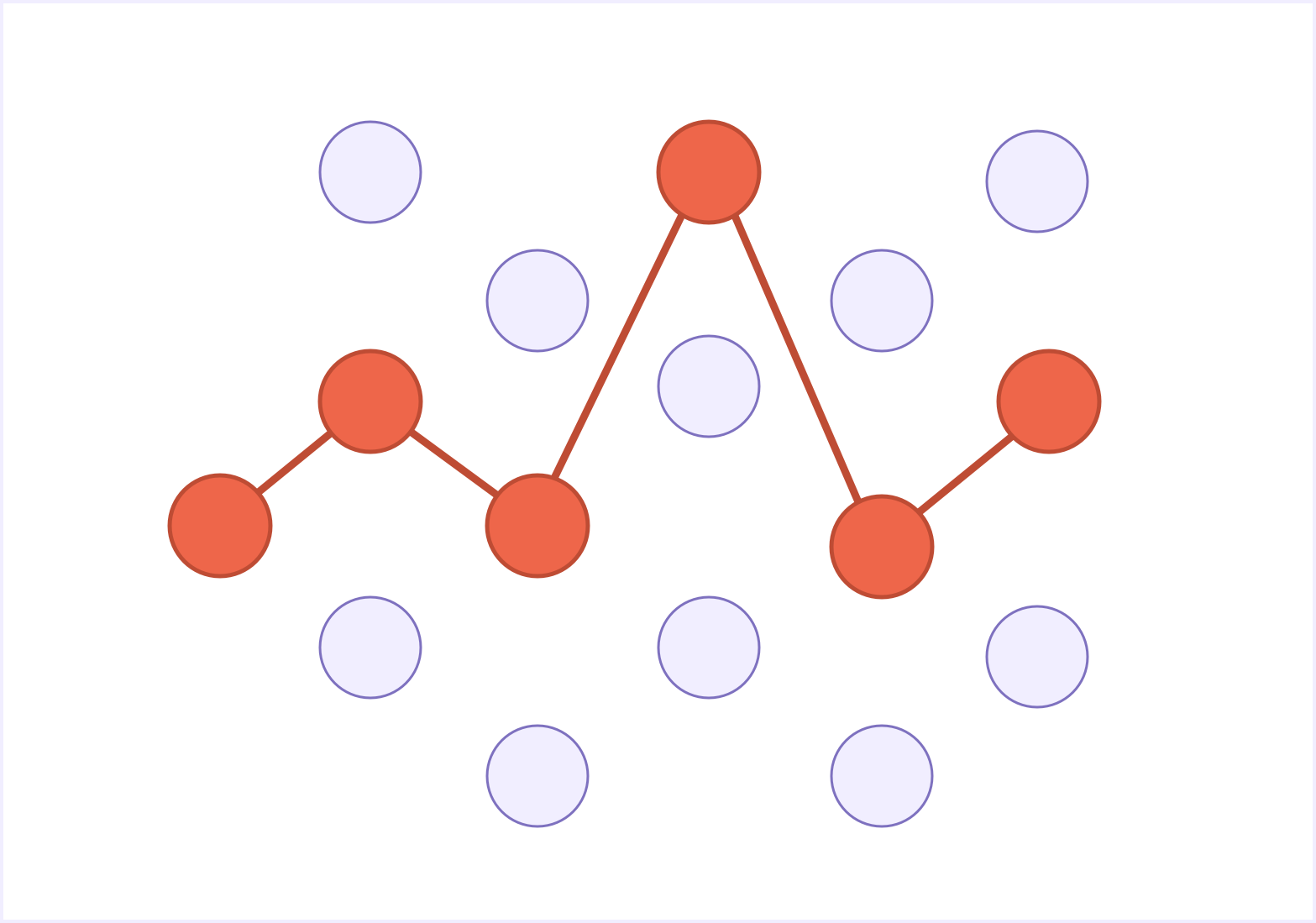

Once you've completed your Lean Canvas, the next job is to define a Critical Path.

The path to shipping your validated MVP with the fewest number of steps is your Critical Path. It's a list of steps and milestones that must be reached in order for validated learning to happen, and ultimately, to successfully launch your project.

For better or worse, World War I provided the first practical market for powered aircraft. The flying aces of WWI proved that not only did airplanes provide military superiority, they were also practical to build, maintain, and operate. There was a market for aircraft, and the military aircraft of WWI were the first products to get to that market.

The Critical Path for commercial aircraft developed in the frenzy of inventive activity during and after WWI might have looked like this:

- The airplane must be stable and controllable.

- It must be capable of flying several hundred miles without refuling.

- It must be able to carry 8-12 passengers and their luggage.

There's nothing in the Critical Path about GPS navigation, in-flight beverage service, or adjustable seat backs. Those refinements all came later. The Critical Path is focused on providing a safe, reliable way to get from point A to point B faster and more directly than can be done on land.

In the same way, your Critical path should list out the most basic requirements for getting your customers from point A (having the problem) to point B (not having the problem).

While there is no one-size-fits-all solution for Minimum Viable Products, there are patterns that you can follow to increase your chances that your product will be viable and will one day grow up past the "minimum" phase.

- Validated Learning

- Lean Canvas

- Critical Path

- The Build-Measure-Learn Cycle

Following these practices will help you build the right product to solve the right problem for the right people at the right time. Rather than having to go out and hustle for customers, you'll be building your market into your product.